The file size of an iTunes song is only a fraction of its CD counterpart because it has been compressed discarding data in the process. Is the audio quality degraded? More than a year ago I devised a test to see if we can hear differences between the original and the compressed version. Here are the conclusions after analyzing data from more than 500 test takers.

This article is about empirical results. I will present them in a moment, but first allow me to rebuild the context in which they were obtained in order to interpret them correctly.

Let’s make sure we all understand the words ‘lossy’ and ‘lossless’ in the context of audio in the first place. Assume a CD is a faithful copy of the music recorded at the studio. If we want to transfer the music it contains to a portable device like our phone or mp3 player, we ‘rip’ the CD to our computer using a software application like iTunes, a popular example. By default, when the CD content is transferred to your music library, iTunes will significantly compress audio files to a fraction of its original size to save storage space, discarding part of the original data in the process. We call this a lossy compression method of codification—or lossy codec for short. If you want to preserve all the data contained in the CD, you may choose a lossless codec. FLAC and Apple lossless are good examples of the latter. No data will be discarded in the process, but music files will take up much more space.

Why is a lossy codec the default option in iTunes? Aren’t we sacrificing fidelity for convenience? Well, the truth is lossy codecs are really smart at deciding what data to discard. They are based on knowledge about how our ears and brain perceive what we hear—the science of psychoacoustics. When using a good lossy codec like iTunes plus, experts are confident that we will not notice any sort of degradation in the music. But will we?

The moment we read ‘lossy compression discards data to reduce file size’ we can’t help but think something bad is happening. However, most of the music we have access to through streaming and the Internet is compressed using a lossy codec—iTunes and other music services compress files to about 1/6th of their original CD size. That is quite a significant amount of data thrown away in the process. Shouldn’t we be able to detect the loss? It seems reasonable to think that we should, given the ratio.

To address the issue of compression vs. quality, I set up an online test that compared CD audio vs. AAC 256k VBR, the high-quality lossy codec used by iTunes. I wanted to offer people the chance to decide for themselves if discarded data necessarily meant degraded sound quality, and I could also gather valuable information that could reveal some interesting facts. Part of the motivation for this project came from what I considered unjustified (and not always unbiased) criticism on the supposed low quality of lossy codecs to justify the need for solutions like High Resolution Audio (HRA) or initiatives like Pono. Many of their enthusiasts boast that lossy and lossless compare as ‘night and day’, and some even go as far as considering CD audio ill-qualified for audiophile ears.

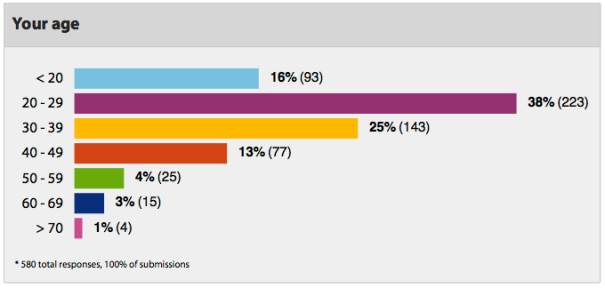

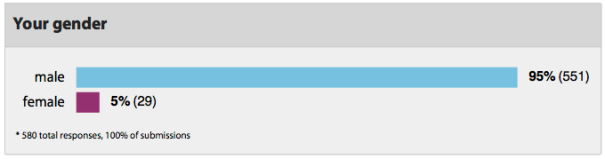

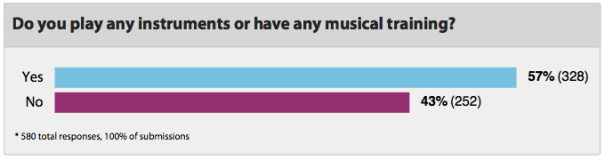

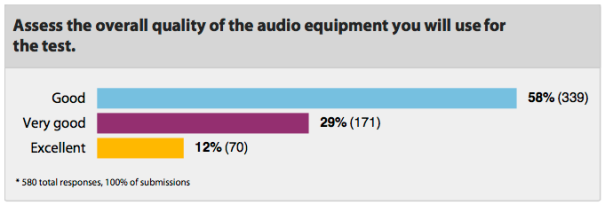

The test was available online for almost a year, and I was able to collect 580 submittals of results from a varied population of test takers to whom I am deeply grateful. They started by answering a brief survey about their age, gender, whether they had any musical training or not, the quality of the audio equipment they would use to take the test, and their location. Then they went on to the blind test. They had to choose a musical clip and listen to a series of 16 trials composed of two sections, A and B, one being CD quality and the other, AAC 256k VBR. In each case they had to decide whether A or B was CD quality. They were offered a way out at the 8th trial if they got tired, but most participants went through the sixteen trials, providing more accurate statistics. There is an offline version of the blind test available on this site if you are interested in taking it yourself.

Meet the test takers

It was nice to see that people of all ages were engaged with the challenge, showing that we do care about how to get the best experience possible out of the pleasure of listening to the music we love.

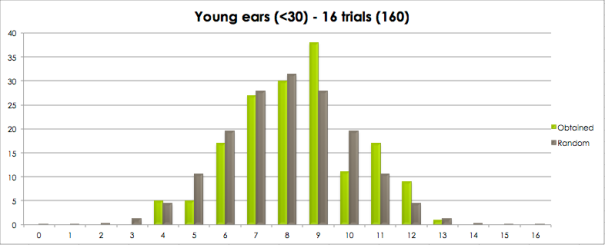

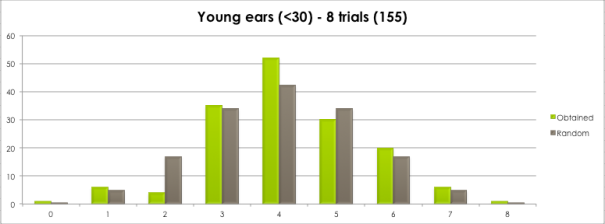

Our ability to perceive high frequencies decreases with age. I thought it would be interesting to see if the young performed better in the blind test. We are about to find out.

Looks like the issue is mostly a male thing.

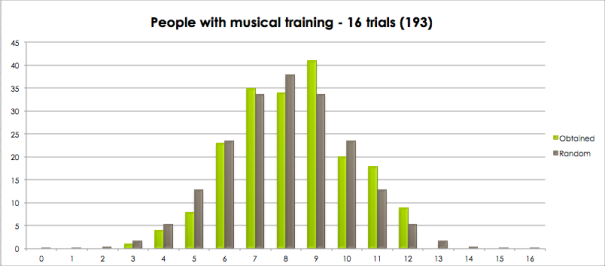

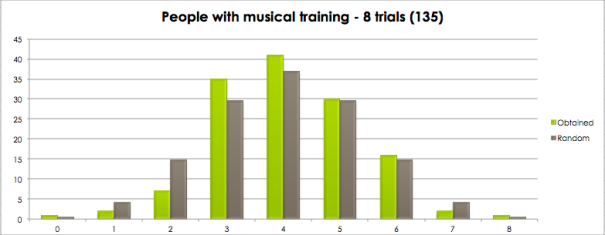

Could any sort of musical training lead to better performance?

If the differences in the audio quality of the formats were expected to be really subtle as I was convinced, not only the listener’s ears but also the audio equipment used would be a key factor in the results.

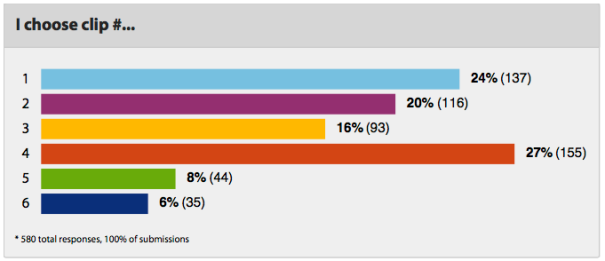

As I said, I offered a choice of music styles to make the blind test more engaging: rock, jazz, blues, soundtrack, classical… I was glad to see that all six clips got finally tested, although it was fairly easy to predict that #4 would be the most popular…

Music clips: #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6

(Note: these are fast-streaming low-quality mp3 samples)

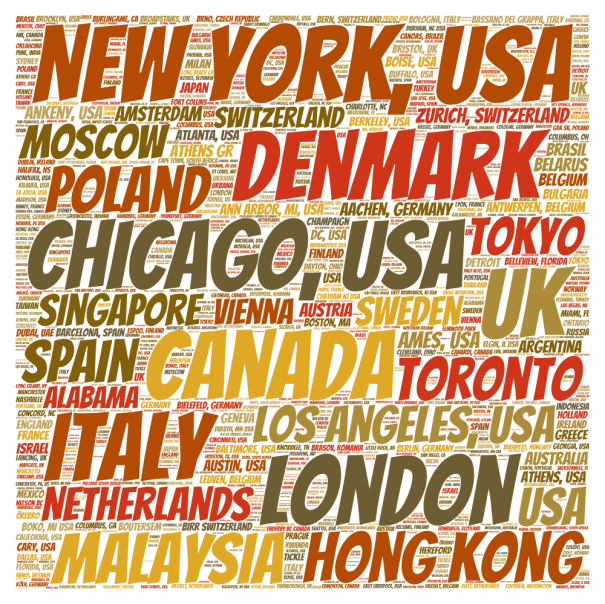

One of the nice outcomes of this project has been reaching so many corners of the world. I have generated a word cloud with most of the locations were the test was taken (click to zoom).

O.K., so, what does this large and varied sample of people say about our ability to tell CD and iTunes plus apart? As I said earlier, the audible differences between the two formats are so subtle that we may state the following

O.K., so, what does this large and varied sample of people say about our ability to tell CD and iTunes plus apart? As I said earlier, the audible differences between the two formats are so subtle that we may state the following

NULL HYPOTHESIS: The people who took the test performed no better than they would if they had chosen their answers at random.

Do the data obtained provide enough evidence to reject this hypothesis?

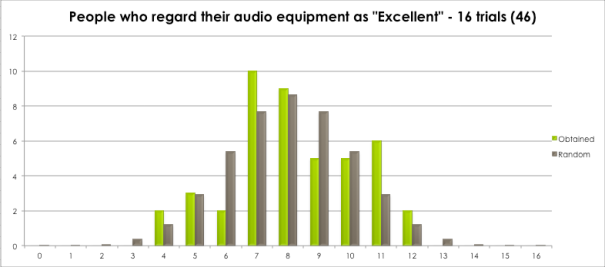

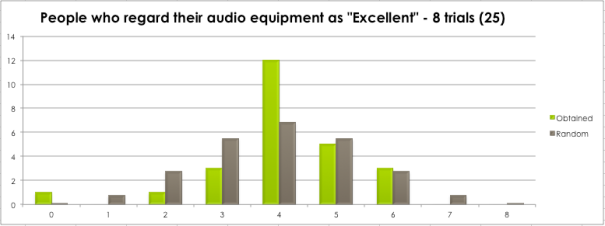

We proceed as follows: we gather all the scores and compare their frequencies (the number of people who obtained that score in the corresponding category) with the frequencies we would expect if people were just picking their answers at random. Then we analyze the deviations from the expected results using a very common statistical proof: the chi-squared test. This test tells us the probability of obtaining such a distribution if the null hypothesis is true (p-value). A p-value of less than 0.05 is commonly required to reject the null hypothesis. In our case, a sufficiently low p-value would provide statistical evidence that people could tell which format they were listening to.

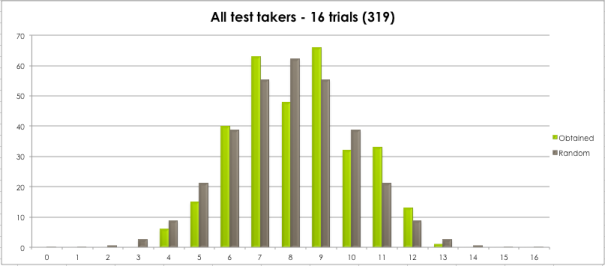

In the following charts, green bars indicate the frequencies obtained and brown bars, the frequencies expected, for each value of the score. There are two charts in each category, one for each version of the test: full (16 trials) & shortened (8 trials). The p-value of the chi-squared test is indicated in each case.

Chart #5: Chi-squared test p-value: 0.92 (>>0.05) The sample is small. The chi-squared test is not very reliable

Chart #6: Chi-squared test p-value: 0.040 (<0.05) The sample is too small. The chi-squared test is not reliable.

Notice that, despite deviations, both distributions have similar bell shapes. Furthermore, all reliable p-values are in favor of the null hypothesis stated, some of them in high agreement. So, based on the data obtained, the most reasonable conclusion is that we can’t hear the difference between CD audio and iTunes plus. And this is true in all the cases considered—being young, with our sense of hearing at its peak, having musical training or using excellent audio gear doesn’t seem to help.

Individual cases

Do these results mean there are no exceptions to the rule? Of course not. In fact, one early participant from Limmerick PA took the test twice and got a score of 15/16 in each try. Such a result is highly improbable, and suggests he was indeed able to spot the differences in the samples he tested (a chance of 1 in 10,000,000 for 30 successes in 32 trials!). So we may have found one single pair of ‘golden ears’, after all, among the test takers! This is what he wrote as a comment in his second try:

This one was much harder to differentiate than sample 6. Honestly all the other samples I do not think I could tell them apart. They are too narrow and lack the sharp percussive elements that are required in the sampled portion. I’m also not as confident on my ability to discriminate on this sample vs the previous one. There are very short sections which I know are different, in each version, but I’ve been at this for almost 2 hours. So I am just going to stop here.

Here we have somebody with trained ears who knew were to look for differences and (presumably) used outstanding audio equipment, and still the challenge demanded from him a great deal of concentration. To me, his comment makes quite a case in favor of the high quality of the lossy codec used.

There were some other examples of good performance. Scores of 12/16 or greater (and to a lesser extent 7/8 or greater) are a good start in favor of your ability to discriminate (p<0,05). But to prove you can, you must get high scores repeatedly for consistency. A participant from Thunder Bay, Canada, the only one who took the test three times, got scores of 12/16, 9/16 and 7/8. The probability of getting this result or better by chance is as low as 8 in 1000, but results like this can be expected in a sample of 580. A few more participants who also got high scores either failed to perform sufficiently well in a second try, or simply didn’t take the test more than once.

Finally, low scores are also worth considering as a sign of discrimination, because they are as rare as high ones. Anyone getting scores equal or less than 4/16 or 1/8 repeatedly would be proving he or she can discriminate, but with the odd outcome of considering the lossy codec higher quality than CD. In any case, no consistent low scores were observed in the sample.

The bottom line

AAC 256k VBR codec delivers excellent compression quality that will suffice for most of us. If you think you are a rare bird with golden ears, test yourself blind to know if you truly are before worrying about the quality of lossy compression codecs. Odds are in favor that you’ll be disappointed.

Questions and comments welcome!

Yes, I vaguely remember doing this test. I think I may have given up and guessed answers after I realised I couldn’t really tell a difference.

I still like cd’s for the physical format, booklets and listening to single albums, rather than an “mp3 player” of some sort with hindreds of songs. But I do use the mp3 player or smartphone/spotify quite often. I rip cd’s using the XLD application on my Mac, which allows ripping to several different codecs all at once. For mp3/aac/vorbis files, I use slightly higher than 256 kbps VBR (just for peace of mind). Good test!

Ah I remember doing this test. At the time I had rather cheap headphones I was using and now I kind of wish I had tried this on my home theater instead. I wonder if it’s easier to talk the difference with a much more powerful system available.

What?

This was a cool test. I eventually figured out what difference to listen for on MY setup at home– should’ve taken it again. I agree with your conclusions though. Thank you for doing all this work! Really interesting.

The reality is most people don’t know what they are listening for, the other thing is most people won’t have the equiptment to be able to show up the loss in depth and width of sound stage, the loss in high frequency extension or the transparency of the midrange. And in any case regardless of cost or quality, headphones are the worst devices possible to use in a test like this. That being said that if you listen to 95% of your music through mobile devices through headphones. And the other 5% of the time is through a moderate quality stereo or home theatre while standing in another room then there is no point reaching for the lossless,!the 256k is the only choice in that scenario. In fact for 98% of the population 256k compressed is flat out the best choice. If your not in a situation to appreciate the solidity of the no loss audio there is no point having it. The idea that this test proved there is no difference in lossless to compressed or even that we can’t tell is totally absurd. It simply proves that compressed audio is perfectly acceptable for the majority of people in the majority of circumstances. It’s always been like that and it always will be. Given the right equiptment, setup and training the difference is night and day. The reality is that the majority of us will never be in that situation. So compressed music has a very strong position for the future of audio delivery and it’s only going to get better with time.

I remember hearing very very subtle differences in the samples even on my cheap headphones when listening again and again. But in no way I was able to identify which one was loseless and which was lossy or just pick the better sounding one. I doubt anybody could identify 256 kbps VBR AAC without comparison to loseless rip of the same song.

I have to question your conclusion. You made various correlations between obtained scores vs expected random choices and then conclude that people can not differentiate between the formats? Secondly, the mastering of the Adele clip was horrendous and thus very difficult to differentiate. Seeing that most people chose that song, I think it might have affected your results. It would have been equally difficult to differentiate between low complexity tracks (the clips featuring a few string instruments). When I did the test there was no option between 8 or 16 clips (or I did not notice it), so I attempted two 16-clip tests. That was a very fatiguing exercise. I would suggest smaller tests (8 at most) with participants having to do at least 2 different tracks (with a break in between). Last but not least, in what format was the CD-quality clips. To my ears neither options sounded like good CD quality.

Very well done.

I guess that this proves is even if you can hear the difference it doesn’t matter on an economic scale. Regardless of the cost of storage of one file, with the size of some libraries that content providers are hosting, the savings in space and bandwidth versus the gains for so very few people make the lossy codec an obvious choice for distributors.

Thank you for doing this.

Thank you for dedicating your time to conduct this test. I am 47 and have loved rock, blues, pop and country music since I was a young boy. I have played guitar on and off since I was 9 years old and also played in a rock band. I enjoy listening to my music loud and have a better home stereo, car stereo and headphones than most people but not to the level on an audiophile. I have always bought records, tapes and then CDs. I loved the idea and conveinience of downloading music onto my iPhone. I downloaded the latest various artist pop album from iTunes and was very disappointed with the sound quality. After researching on the internet I discovered from what others were saying, that the iTunes quality is very poor so I went out and bought the same album that I had downloaded on CD just to compare the difference. I could not hear any sound improvement on the CD and after more research on the internet I discovered that most of the modern pop music is recorded at maximum levels for people listening with poor quality systems, speakers and headphones. For many of us who listen on reasonabley good quality systems, this is a major disappointment as the music sounds distorted and looses its dark and light shades. I suspect many people are similar to myself who haven’t bought any music that has been recorded in the last 20 years. We have bought ourselves an iPhone, downloaded iTunes and gotton all excited about downloading music straight onto our phones. Searched all the music available on iTunes and decided to download some of the latest music. We then compare the quality to that of our CD collection that was recorded in the 70s or 80s only to disappointed assuming it is the quality of the lossless format when in reality it is the way a lot of the latest music is recorded. If you buy the latest various artist CD and play it loud then select AC/DC Back in Black from your CD collection and play it at the same volume you will hear exactly what I am talking about and you will certainly not need to do any blind testing even on the deaffest ears as the difference is like night and day and is instantly obvious. We need to direct out listening frustrations to recoding companies rather than to iTunes. As this test shows, the majority of people really can’t tell any difference between the CD and the latest iTunes lossy formats. We should all be greatful and thankful to Apple and iTunes for developing this technology and allowing us to keep our record collection in our pocket.

I don’t pretend to have super hearing-in fact at my age I have the typical high frequency loss (I’m almost 65 above 12,000 hz it’s sounds of silence), but I have taken quite a few of these blind tests and even though low quality compression is easy to discern-when comparing high quality lossy to lossless–I almost always prefer the sound of the compressed files. Not sure what this means-maybe it’s the reduction in unnecessary sound–though i make no claim to be that discerning in my hearing. But for whatever it’s worth I usually get at least 5 out of 6 as lossy and the odd choice is actually lossless. I use good quality headphones or my home stereo which is probably average quality for anyone who listens to music seriously. Anyhow, in my own particular case, I find lossless is only good for storing files that I may wish to use to burn my own cds at some point in time, but for everyday listening pleasure–I actually prefer high quality lossy–I really can’t explain why but to me it sounds slightly better. (clearer, cleaner might be more appropriate words)

I assume that this test was just a blind A/B test and not a true ABX? The problem with a blind test is that the listener KNOWS there’s a difference and is predisposed to hearing (or imagining) it. ABX, by forcing the listener to identify A or B as X, eliminates even that possibility of error. The guy who got 15/16 would probably not have passed an ABX test (nor would any of the so-called “golden ears”). Anyone who thinks the difference is “night and day” is in for a rude shock in a properly moderated ABX test.

Thank you for your comment, Greg. I don’t see the problem with the A/B testing mode, though. Of course you know the samples are different, but you would not do better than choosing by chance unless you were effectively spotting some difference. Of course, the people who got high scores in my test would have to undergo further testing with improved conditions to definitely prove themselves they can consistently hear the difference. I totally agree with what you say in your last sentence. There is no doubt that claiming “night and day” is utterly preposterous.

The difference is night and day but only to unique individuals with extraordinary hearing and years of training/experience in critical listening. Car audio competition sound quality judges would be an example. Studio audio engineers are often contracted for important meets. Average person doesn’t know what harmonics do for music so how can they miss what they can’t appreciate. Good for them cause ignorance truly is bliss.

I don’t know anything about different listening environments. I read here that most people took their tests on headphones. Okay. So how about live performance environments where people dj prerecorded music, i.e. clubs, dancehalls, dingy underground events, rave concerts, warehouses, etc., or just small rooms with small pa speaker systems/? I would really like to know; my itunes library is huge, I’ve been building it for years and most people say that flac vs aac is day vs night in such environments and such loudspeaker equipment. If I made a mistake in my investment and all the time the I’ve put into labeling id3 tags on my performing music software, are there any solutions? Thanks in advance!

It really comes down to be willing not to fool yourself. Our brain can play amazing tricks on us. Those people who say flac and aac are day and night would really blush if they performed a blind test. If you want to play a trick on them, just convert some of your mp3’s to flac and let them read the file extension. They will immediately find they sound much better, which is just a product of their willingness to prove their point.

I was at a party once and was talking to somebody who worked for Dolby investigating what people could detect. What he was saying seems consistent with your results. Most people can’t tell the difference, but there are some people who can tell the difference between even slightly compressed files and the originals.

Another thing that everybody should keep in mind is that even low bitrate, non transparent encoding (take for example 128kbps MP3) : is still much more respectful of the original recording than the best new phonogram played on a good turntable. Less noise, less distortion, better separation, better dynamics.

All audiophiles who are using 100k$ gear to play phono, are actually using a source worst than a bad quality MP3, the kind of MP3 that I would never play on my connected speaker.

[…] too; 60% of them reported using audio systems costing $1,000 or more. And this is just one of numerousexamples around the […]

So, this is really old, but how can you have VBR 256K? VBR means Variable! If it varies, then all the samples can’t be encoded to the same bitrate (256K). Perhaps you/iTunes meant CBR, or ABR? AAC VBR typically offers “Quality levels” 1-5 and uses as many bits is it deems needed to get those 5 levels of quality. I encoded ~2000 songs with VBR Q5, highest quality, considered “transparent” (indistinguishable by experts with reference equipment). The *variable” encoding rate ranged from 105kbps (Hank Williams, I’m so Lonesome I Could Cry) to 288kbps (Paul McCartney, Love in the Open Air) with both the median and average rate dead on 202kbps. 50% of the songs fell between 190-210kbps.

Encoder setting in iTunes had those options. Set the encoder to “AAC”, and choose “Custom settings”, then new window pops up, and there’s bitrate/sampling rate/channel options with the checkbox “Use Variable Bit Rate Encoding”. So…Yes, it can’t really be 256kbps because it’s VBR, but with iTunes, “AAC 256kbps with VBR” could be actual encode setting. If you see only “VBR Q*” with AAC encoder setting, I guess you are not using iTunes.(maybe foobar2000, or something)